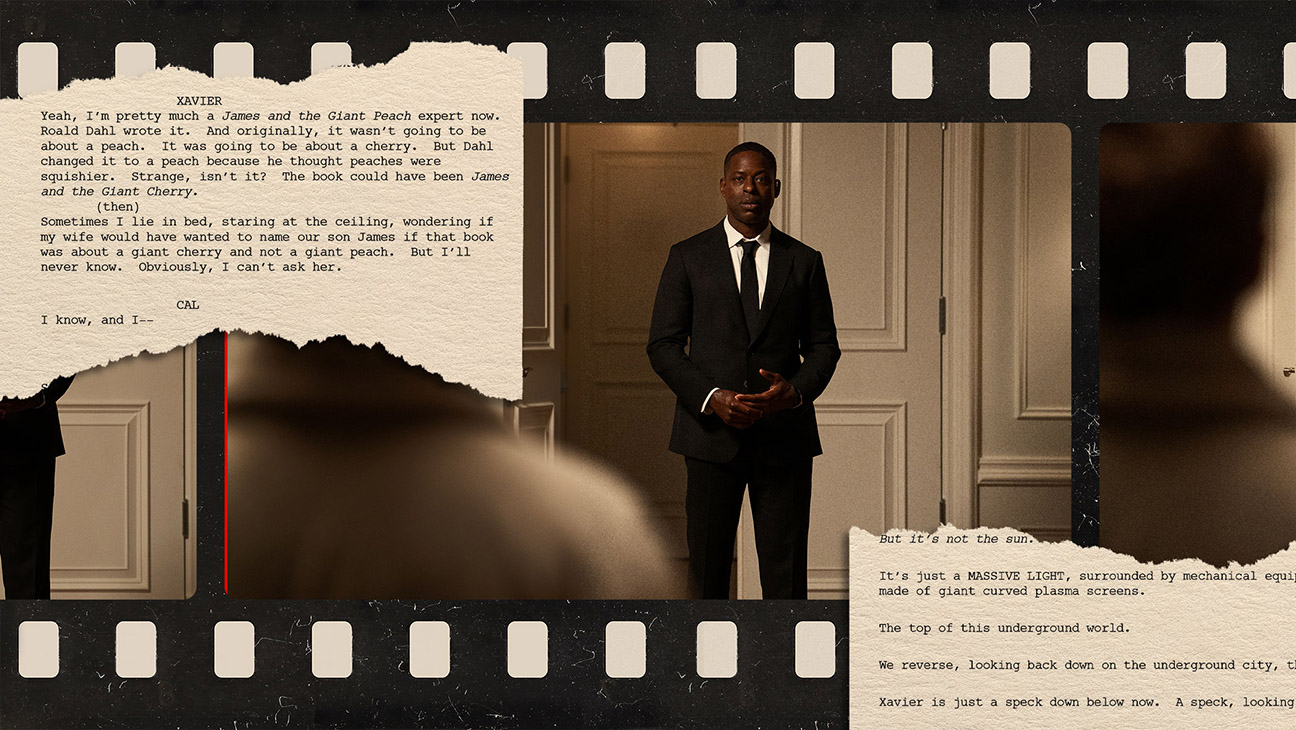

Dan Fogelman became obsessed with crafting a story about the world’s most powerful people after having a meeting with a billionaire a decade ago and hearing a loud bang on his drive home. “It made me think of Secret Service agents and presidents,” he says. Fast-forward to Paradise, where a dystopian community has been built beneath a mountain in Colorado in preparation for an apocalyptic disaster. The president of the United States (James Marsden) is mysteriously killed, and Xavier Collins, a Secret Service agent (Sterling K. Brown), has to figure out what happened. In the final sequence from the pilot, Collins sprints down the street as flashbacks set up the show’s central mysteries.

Fogelman selected this sequence because of how much these pages differ from what’s onscreen. “So much of the writing is done in preproduction, production and then in editing,” he explains. In the episode, this monologue ends with the line, “I’ll forgive you when I can sleep again, and I’ll sleep again when you’re dead,” instead of what’s written. On set, the crew shot various versions of Brown’s monologue, “and when Sterling delivered that one for the first time, I remember they yelled, ‘Cut!’ and Sterling said, ‘Wow! That shit hits different.’ ”

Disney

Brown’s monologue about James and the Giant Peach, and how the titular peach was originally a cherry, was the result of Wikipedia research. “Sometimes I wish there was more method to it,” Fogelman says. “I had named the child James, and he was reading a book, and I said, ‘Oh, I wonder if there’s an anecdote about James and the Giant Peach that I could come up with.’ “

Disney

In the original conception of the episode, Fogelman wanted viewers to see Collins run past everyday things, “and at the end of the episode, you would reverse his run and start seeing the B-side of what’s weird about these places. I had a gardener, [and] it looks like he’s watering a lawn. Then, when Xavier’s returning home, you realize he’s painting [the grass].” Due to production constraints, these moments of crafting the artificiality of the space changed. Instead, beautiful ducks at the beginning of the episode are revealed to be mechanical.

Disney

This kitchen scene didn’t make the final cut, though it was shot. “The kids were great, but we were building toward an ending, [and] what we realized was it was more powerful to just stay with our great actor [Brown] on his beautiful monologue than to cut to the scene itself,” Fogelman says.

Disney

These final lines of dialogue were ultimately omitted from the episode, even though they made an initial cut. During test screenings, Fogelman found that some viewers were “starting to jump on Carl (Richard Robichaux) as a potential suspect, [when] it was meant to speak to the monotony of this world and just be the final punctuation on this [being] a bunker that’s underground and every day is the same.”

Disney

As a screenwriter, Fogelman has learned that network execs, actors and other readers can have “a tendency to push through stage direction really fast and almost miss really important stuff. So once in a while, I will use italics or bold or underlines just to make sure the reader’s eye goes to it.” Another tactic Fogelman employs to enhance readability is “really spacing out stage direction. It creates extra page length, which writers are often fighting against, but I have found that if all that stage direction was just written in prose — which it easily could be — it takes you out of the rhythm. Just one line at a time of stage direction sometimes can help the reader see it a little bit more.”

Disney

In the final version of the episode, we do see numbers written on the cigarette as well as a mysterious symbol. That decision to show the inscription on the cigarette was, again, a reality of production. “I don’t know that I knew what was going to be on the cigarette [in the first draft],” says Fogelman. “Once I had the whole season broken, I could go back and plug in what was on that cigarette. But the other part is, in execution, what’s it going to look like if I just have him look at a cigarette? How would you ever know that there’s something [on] it? Is it just going to read, like, is he thinking he wants to smoke?”

This story first appeared in a June stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.