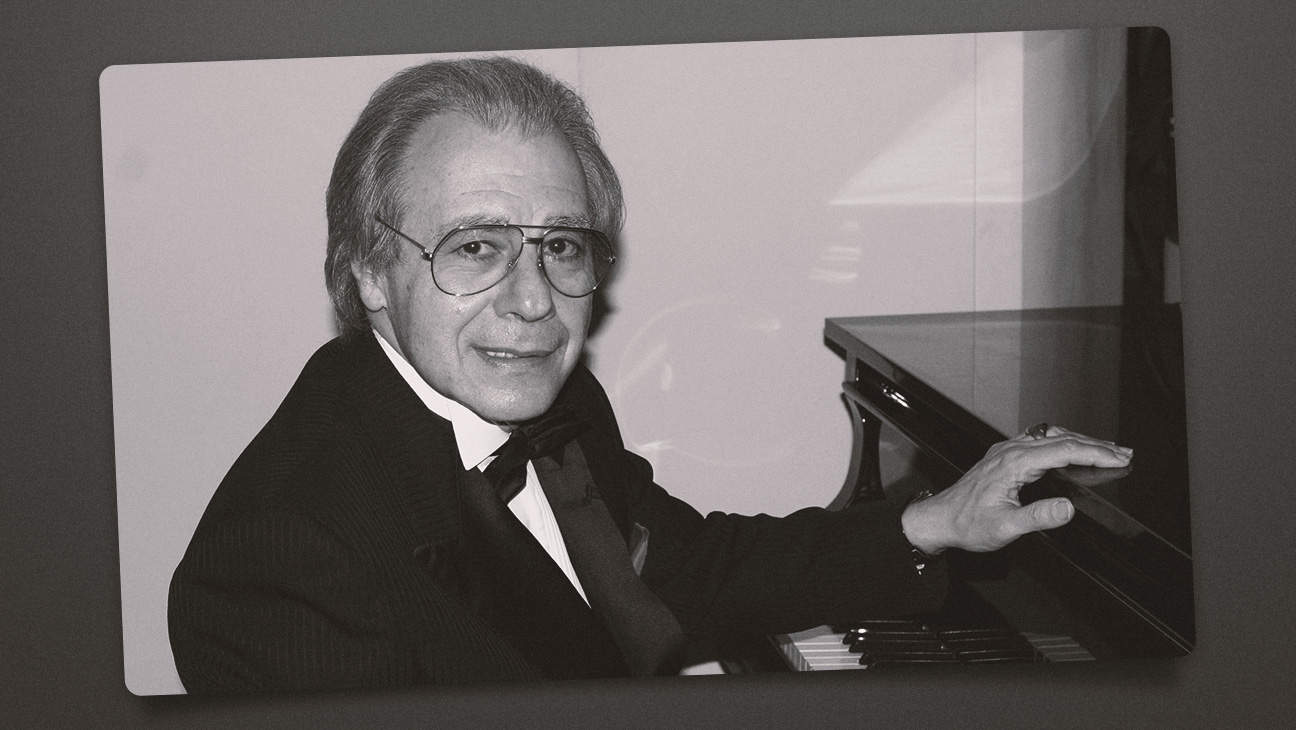

Lalo Schifrin, the six-time Oscar-nominated composer, pianist and conductor renowned for his electric, jazz-infused themes and music for Mission: Impossible, Mannix, Starsky & Hutch and Bullitt, died Thursday, his son Will Schifrin told The Hollywood Reporter. He was 93.

Schifrin, who received an honorary Oscar at the Governors Awards in November 2018, lived for decades in a Beverly Hills home previously owned by Groucho Marx.

A native of Argentina whose father was the Buenos Aires Philharmonic concert master for more than three decades, Schifrin was trained in the world of classical music before being hooked on American jazz when he was a teenager.

He artfully blended the two genres, and the combustible energy and rhythmic vitality of his compositions were especially well-suited for action-suspense movies and TV shows.

The workaholic Schifrin received Oscar nominations for his scores for Cool Hand Luke (1967), The Fox (1968), Voyage of the Damned (1976), The Amityville Horror (1979) and The Sting II (1983) and for the song “People Alone” from The Competition (1980).

He scored Dirty Harry (1971) and the sequels Magnum Force (1973), The Enforcer (1976), Sudden Impact (1983) and The Dead Pool (1988), all starring Clint Eastwood — the filmmaker presented him with his Oscar — and served as the composer on all three of the Rush Hour films.

Schifrin had Ray Charles perform with a symphony orchestra for The Cincinnati Kid (1965), and he provided the classic saxophone-laden car-chase music for Steve McQueen’s Bullitt (1968).

His résumé also included work on Coogan’s Bluff (1968) — that kicked off his long association with Eastwood and director Don Siegel — Kelly’s Heroes (1970), Charley Varrick (1973), The Eagle Has Landed (1976), Telefon (1977), The Nude Bomb (1980), Black Moon Rising (1986), Money Talks (1997), Something to Believe In (1998), Tango (1998), Bringing Down the House (2003) and The Bridge of San Luis Rey (2004).

His cool, percolating Mission: Impossible theme, set to an unusual 5/4 time signature and commissioned for the fabled CBS espionage drama that bowed in September 1966, netted Schifrin one of his four Grammy Awards and one of his four Emmy noms. It still serves as a vital link to the Tom Cruise movie franchise.

Schifrin said it took him just three minutes to put the theme together, and he composed it without seeing any footage from the show.

“Orchestration’s not the problem for me,” he told the New York Post in 2015. “It’s like writing a letter. When you write a letter, you don’t have to think what grammar or what syntaxes you’re going to use, you just write a letter. And that’s the way it came.

“Bruce Geller, who was the producer of the series, put together the pilot and came to me and said, ‘I want you to write something exciting, something that when people are in the living room and go into the kitchen to have a soft drink, and they hear it, they will know what it is. I want it to be identifiable, recognizable and a signature.’ And this is what I did.”

The Mission: Impossible opening credits showed a match lighting a fuse that burned superimposed over quickly-cut scenes from the episode. Schifrin wrote music for several episodes as well, and an M:I album proved quite successful.

An inspired Bruce Lee worked out to the show’s score in his gym in Hong Kong before signing Schifrin as the composer and orchestrator on Enter the Dragon (1973). As a bonus, Lee gave the musician his first martial arts lessons, for free.

Schifrin concocted a jazz waltz in 3/4 time for the theme to the Mike Connors series Mannix — also produced by Geller — and played the Moog synthesizer on the opening music for another 1960s’ CBS drama, Medical Center.

Schifrin also was responsible for the themes for T.H.E. Cat, Petrocelli, Starsky & Hutch, Bronk and Most Wanted. And his “Tar Sequence” music from Cool Hand Luke was adopted by ABC affiliates for their Eyewitness News broadcasts.

Born Boris Claudio Schifrin on June 21, 1932, he began playing the piano at age 5. His classmates exposed him to jazz records when he was about 16, and he became “totally absorbed in that music,” he recalled in a 2008 interview for the Archive of American Television. “It was like an illumination, a very important moment in my life. I converted to jazz.” However, jazz was considered “immoral” back then, and he had to listen on the sly.

He studied music and law for four years at his hometown University of Buenos Aires, then received a scholarship to the Paris Conservatory of Music in 1952, studying classical music under famed composer Olivier Messiaen.

“I had a double life,” he told The Telegraph in 2004. “I would study at the Conservatory during the day and play in jazz bands at night in places like the Club Saint-Germain. Messiaen didn’t like jazz, but he was a very nice man, a Catholic mystic.”

In 1956, Schifrin returned to Buenos Aires, formed his own jazz band and got involved in writing music for TV and radio programs. A year later, he won Argentina’s equivalent of an Oscar for his score for El Jefe.

With Dizzy Gillespie and his all-star band (including Quincy Jones on first trumpet and Phil Woods on alto sax) in town for a concert at the U.S. Embassy, Schifrin conducted his group from behind the piano during a reception to honor the jazz great.

The trumpeter approached Schifrin and asked, “Do you write all these charts, all these arrangements?” he recalled. “I said yes. ‘Would you like to come to the United States?’ I thought it was a joke.”

Schifrin arrived in New York City in 1958 and played piano in a Mexican restaurant until he was invited by Xavier Cugat to write arrangements for his show and tour with his orchestra.

He finally reconnected and signed with Gillespie in 1960, performing on a hit album, Gillespiana, for Verve Records, which was later purchased by MGM. He also arranged jazz LPs for the likes of Stan Getz and Sarah Vaughan.

Inspired by the movie work of such composers as Henry Mancini and Johnny Mandel, Schifrin employed his MGM connections and headed to California in 1963.

His first Hollywood gig was for the African-set film Rhino! (1964), and he scored several projects under Stanley Wilson at Universal Pictures, including the 1966 bomb-on-an-airplane NBC telefilm The Doomsday Flight, written by Rod Serling.

Schifrin also scored David Wolper documentaries, including The Making of a President: 1964 (1966), for which he received an Emmy nom; The World of Jacques Cousteau (1966); and The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1968).

Throughout his career, Schifrin conducted a number of the world’s top orchestras, including those in London, Vienna, Los Angeles, Israel, Mexico City, Houston, Atlanta and Buenos Aires.

In 1987, he was appointed musical director for the Paris Philharmonic Orchestra, which was formed for the purpose of recording music for films, and held the post for five years. Schifrin then conducted a 1995 symphonic celebration in Marseilles, France, to mark the 100th anniversary of the invention of movies by the Lumiere brothers.

His longtime involvement in the jazz and classical worlds came together quite nicely in 1993 when he was featured as pianist and conductor for the first of his several “Jazz Meets the Symphony” albums.

Schifrin, who received the BMI Lifetime Achievement Award in 1988, recorded dozens of albums, many on the Adelph Records label run by his wife, Donna. He also was the principal arranger for The Three Tenors’ World Cup concerts.

In addition to his wife and son Will, a TV writer (The Fairly OddParents), survivors include another son, Ryan Schifrin, a writer-director (Abominable); a daughter, Frances; and four grandchildren.