The following is excerpted from Matthew Specktor’s new memoir, The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood, about growing up in Los Angeles, with his father — CAA super-agent Fred Specktor — and writer mother, Katherine, surrounded by industry players, movie stars and left-wing activists. In 1981, the year Matthew turned 15, Fred decided to change his life. Before he did, he said something that would change Katherine’s life too, a casual remark he made one night at dinner.

***

“Maybe you should write a script.”

My father takes a thoughtful sip of wine. He stares at my mother across the dining table, fork resting sideways across a plate of angel hair that appears to have been licked almost clean. “What do you have to lose? It’ll give you something to do while you’re sending out stories.”

“Do you think?” She swipes her tongue to dislodge a fleck of basil. “What do I know about writing a script?”

“What does anyone know?” my father says. “You think the writers my office represents all started out as experts?”

As in the movies sometimes, life can happen out of order. Cause and effect, action and consequence. Six months before my father leaves, he offers a solution to a problem that doesn’t yet exist, throwing a life preserver to a woman standing on dry land.

“What about rewriting a script?” he says. “How would you feel about that?”

I believe my father is acting in good faith. My mother is an artist. She has been in her secret heart for years. Why wouldn’t he encourage that?

“You’re a writer,” he says. Irrespective of any discontent that may be boiling up inside him, this is an act of support. “You’re as talented as anyone I know. Why not see if you can get paid a little money for it?”

Let’s look at her: a woman of forty-five, still young as these things go, still beautiful and funny. Her once-blond roots have darkened, her complexion has grown a little ruddy — too many hours in the sun, and perhaps the influence of something else — but she remains at the height of her abilities and appeal.

“I suppose I could give that a whirl,” she says, with a little dash of the devil-may-care confidence that hides somewhere deep, deep inside her. “You got a particular script in mind?”

“You know that project we were talking about with Larry Peerce the other night?”

“The prison drama?”

“Yeah,” my father says. “The one with Laddie.” He takes another small sip of wine. “They could use some help with that.”

Ah. Knowing what I will come to know — that after he leaves, my father will worry about her, wracked by the pain he is causing — I know he is paving the way for his escape, but he is also trying to do the right thing. She has gifts. Shouldn’t she use them?

“I’ll have a look,” my mother says, shaking a cigarette from her pack. (What kind of person would he be, after all, if he didn’t support her dreams?) “Is there a copy upstairs?”

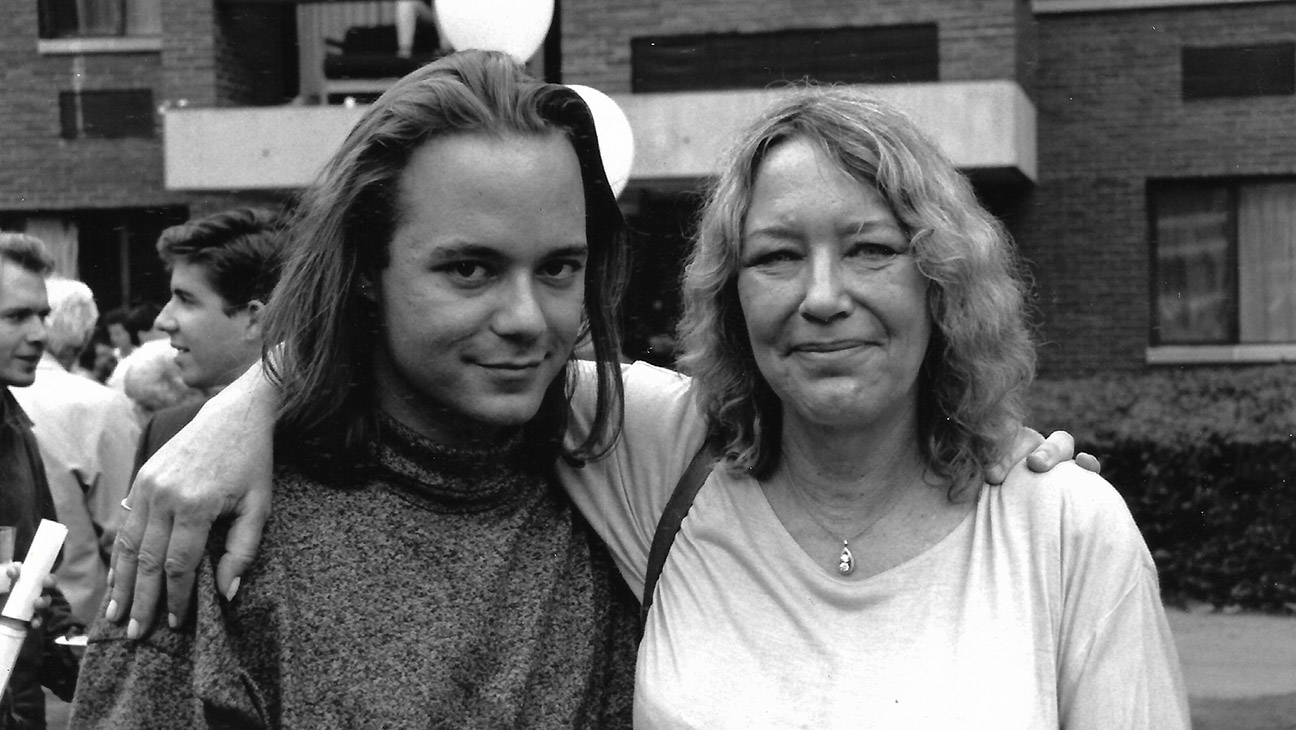

Katherine Specktor

Courtesy of Matthew Specktor

My mother wants to be a novelist. In her heart, I know, this is her deepest wish. This wish she will pass along to me, but in the morning when she rises — it is the summer, now, of 1981, and she is able to take a few months off work — she is just a dedicated amateur. Perhaps it might be better to remain thus. “Why not get paid?” says the businessman, unable to imagine an alternate path to validation for an artist or to understand that money can hinder as well as help, and so each day she wakes up and walks out to the cabana behind the house, carrying her coffee out past the pool and into the room with the clammy brick floors and glass doors, there at last to reckon with her fate. A screenplay is not a novel, perhaps, but it is no small thing to be invited to write one (but is she “invited,” formally, I mean? We shall come to that), and, whatever the medium, no small thing to tell a story in words.

“Mom?”

She goes for it. She doesn’t want to be a screenwriter — the movies are just commerce, where literature is art — but she gives it everything she’s got. The existing script does not have a name. It is based on a segment that aired on Sixty Minutes about a woman named Terry Jean Moore who got caught up in an armed robbery in Florida. The script, written by a woman named Deena Goldstone, is good, my mother thinks — the rub is that Terry goes to prison, where she gets knocked up by a guard — but allegedly the studio is not happy with it. Alan Ladd Jr., who now runs a production entity called The Ladd Company, is not happy, and Larry Peerce, my father’s client who is onboard to direct, is not happy, and so she goes for it, rewriting the script from top to bottom. It’s crazy, really, that they still make movies like this — movies about everyday people, rather than space operas, action dramas, thrillers with high-concept loglines — but they do. Just this year there is On Golden Pond and My Dinner with Andre.

There has been Kramer vs. Kramer and Ordinary People, Norma Rae and The China Syndrome, all recent films that are about human beings, rather than villainous caricatures and heroic cartoons. So is this one, which is why she is happy to write it. And so here she is out in her cold cabana during the summer of ’81, alone with the French doors open, with her desk and the skylight and the tiny refrigerator.

***

And then — it is fall. My mother is holed up in her cabana. Summer is over, school has resumed, and my father is long gone. Hobbled by piercing migraines — one comes on in September and then seems merely to ebb and flow for months, to remain always with me — I take refuge in my room. No one will disturb me here. But there is one thing I notice, as my right eye throbs and I unfold a copy of Daily Variety, having taken to reading the trades now myself. My mother is not just rewriting a script. The situation is a little more complicated than that. My mother is a screenwriter, sure, but she is also —

“A scab.” She thwacks her own copy down on the butcher’s block in the kitchen, the December 7, 1981, issue in which she is front-page news. “They’re saying I scabbed.”

My mother and I have been spending a lot of time together lately. It isn’t to be helped: most nights, we’re alone in the house. Whatever informal custody arrangement my parents have made while the lawyers are grinding away involves my sister being with my dad much of the time and me remaining here with her.

“Is that what they say?” I watch her carefully. “That you crossed the picket line?”

“Yes.” She leans forward, a little unsteady on her stool. “That’s what they say.”

Some part of me will always be here, alone in this room with my mother in cold twilight, seated on opposite sides of this table like a couple of barflies, two cigarettes burning in the ashtray between us.

“Do you think it’s true?” she says. A bottle of vodka sits by her elbow. “Am I a scab?”

“No, Mom.” I listen to her slurry consonants and decide not to poke this bear. “I do not think it is true.”

Alas, however, I know it to be true — even as my mother insists, to me and to herself, that she is just fooling around, that nobody other than my father had invited her to work on the script, so how can she be scabbing? But on April 11, 1981, the Writers Guild of America went on strike. Their dispute with the studios was over residual payments for VHS and Betamax cassettes, the home video market that is just now developing. The strike had lasted for three months, which happened to be the very months in which my mother, a nonunion writer, had rewritten her still-untitled screenplay.

I’m no labor lawyer, I’m a high school sophomore, but as I watch my mother slop vodka onto the table, the bottle as lazy in her hand as a garden hose, it seems to me this is the very definition of scabbing. The strike is why the studio had not been able to hire a professional writer to rewrite the script that is just now entering production in Florida. It is why they hadn’t hired Deena Goldstone to rewrite it herself.

I’m no labor lawyer, but this is how it is. My father had a client, Larry Peerce, a director whose movie needed a rewrite or else it would lose its green light in the fall; my mother was an aspiring writer, an amateur who needed something to do, and my father was a man having an affair, trying to figure out how to leave his wife. These are the facts of the case.

“I’m not a fucking scab,” she snaps. “I’m not.”

The movies will show you who you are. Who you are and who you cannot help becoming. My mother the leftist and the strikebreaker, the screenwriter and the drunk, whose intake has sharply accelerated. This fall, she will take me to see Warren Beatty’s Reds, his movie about John Reed; she will give me John Dos Passos’s The Big Money and Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty to read. Her politics haven’t changed. Only her perspective has.

Everyone thinks they’re the hero, which is a problem not just with the movies but with America, which has no other culture besides its celebrity culture anyway. I’ve been spending a lot of time with my mother, not that I have a choice. But even at fifteen, I understand what she is going through, that she is caught between untenable alternatives — parent, artist, jilted spouse — that bind her into a set of contradictions she cannot possibly resolve.

***

My mother’s movie flops. In the fall of 1982, Love Child receives its title and is loosed into theaters, only to vanish a few weeks later. But my mother by now has other problems.

“Fuck Alvin Sargent,” she snarls, drunk out of her mind once again. “This is all his fault.”

“Maybe you shouldn’t have scabbed, Mom.” Here we are in the kitchen again, leaning over that butcher’s block to which we may as well be chained. “I’m not sure Alvin Sargent is the problem.”

“Are you siding against me?”

My mother has been denied membership in the WGA. A senior member, the writer of Ordinary People who is also the mentor of the person my mother rewrote, has led a charge to blackball her.

“Not taking sides,” I say. If I lit a match, her breath would catch flame like a circus act’s. “But I think — ”

She slaps me, putting her shoulder into it, her arm rigid and jerky like a garden sprinkler.

“Mom — “

I’m so shocked I can only laugh, sinking back onto my stool. She buries her face in her hands and sobs.

“I’m not a writer,” she wails. “I’m not a writer!”

This, I think, is the core of it. My mother is haunted by a quote that appeared while her case was being litigated in public. “It’s a moral and ego thing,” an anonymous member of the Guild’s disciplinary committee had told Daily Variety on December 17, 1981. “You’re not a writer if you’re not in the Guild.” Thus, it is a matter of self-definition. If she is not recognized as a writer, if she is no longer a teacher or an administrator, an activist, or a spouse, then who is she now? What position does she occupy on the grand stage of life?

“I’m not a writer!” She sobs sloppily into her palms while I rub my raw cheek. “I’m not anything at all!”

The movie isn’t bad. Amy Madigan plays Terry Jean Moore, the Florida hitchhiker who gets sent up for a ten-year stretch when her friend pulls a gun in the car. Beau Bridges plays the prison guard who knocks her up, Mackenzie Phillips her lesbian best friend on the yard. Love Child is decent. It is certainly no embarrassment. The Hollywood Reporter thought it was worthy of awards — and Madigan picks one up, a Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer — while the Los Angeles Times found it solid but perhaps better suited for television. The reviews were favorable — “Powerful,” “unsentimental,” “sincere” — but that’s not what this is about.

“Mom.”

This is about self-definition, about who she is allowed to be. Strangely, being blackballed hasn’t stopped her from working. Studios and networks aren’t supposed to hire nonunion writers, but CBS has just signed her on to write a television movie called Princess Grace. The Writers Guild is forced to offer her every protection they do to members, including pension and health insurance. But around town, at screenings and restaurants, she receives angry glares. It’s a moral and ego thing.

“What is it?”

Morality and ego, those twin forces that drive the action not just on the Hollywood stage, but on the national one as well. My father, the businessman, is thriving. It’s a good time to be a capitalist in America. My mother, the strikebreaker, the artist? It is not such a good time for her.

“Dad’s getting married.”

She picks up her glass and throws it at me. It whistles past my ear and explodes against the wall, showering me in vodka and ice.

“Get the fuck out,” she says.

I stare at her a moment, dripping vodka.

“Get out!”

She’s made her own bed, but perhaps no time has ever been a good time for my mother. And there is no betrayal like self-betrayal, that I now know. My parents are regular people, the kind you still see in the movies, as well as the kind who make them. But after my mom has ranted and raved about how my dad betrayed her (“That philanderer! That cheat!”), what is left? Whatever became of the woman who sang “Joe Hill” to me in my crib, the Weavers-loving leftist whose close friend when my sister and I were children was the folk-singer Judy Collins? She sang “Guantanamera,” she sang “Deportee,” she sang “Coal Tattoo,” a union song if ever there was one. In the living room with her friends she sang from the bottom of her heart even as Ronald Reagan’s political career was only just beginning to take wing.

Who, really, betrayed that person? Who? Who? Who?

***

Twenty-seven years later, I stand outside the gates of 20th Century Fox, picket sign raised, chanting towards the sky.

“Hey, Ho, pencils down/Hollywood’s a union town!”

I’m as pro-labor as they come, and now I’m a writer myself, but I feel like a hypocrite. I used to work for this studio, after all. My mother was a scab. If I crane my neck in any direction — a few blocks east of here is the building where I used to work in CAA’s mailroom — I can see the places where I stood on the other side of the line, and the ruins of the world in which I grew up, places that leave me indiscriminately tender. I may as well walk up to the pale plaster walls of the studio that rise above Pico, the central hub of the enemy, and kiss them.

“Hey, Chernin! How much you earnin’?”

I put my sign down. I know exactly how much, after all, and my shift is over. I walk down Pico back to my car, which is parked near the hotel where Bill Mechanic made his speech about middle-class movies almost a decade ago. Depressingly, this strike will only collapse that middle class even further. Over the next three months, the studios will lose hundreds of millions in revenue, and they will use this as an excuse to trigger force majeure clauses. Writers will suffer, as these places trim their overhead and shrink the pie even further, leaving most of us to fight for crumbs. I climb into my car and drive home, looping around up Avenue of the Stars so I can drive past CAA’s new office, the building people call the Death Star in Century City. The Young Turks, now as middle-aged as I am, eventually grew tired of paying Michael Ovitz rent. How small it all seems to me now. How small, really, is this cosmos in which I grew up.

“Hi, Mom. How are you feeling today?”

The MCA building that once seemed so grand to my father is home to just another private equity firm now, too nondescript to notice when you pass it on the street. The I.M. Pei building will soon be converted into a WeWork. And as I’m cutting up Santa Monica Boulevard, two blocks from my childhood home on Warnall Avenue, my mother calls. It’s like she can read my mind.

“Not so bad, honey.” Even the screens are small, these days, like the one I now hold in my hand. “Were you out on the line today?”

“I was.”

“Good for you.” Her laugh is a wan, throaty rumble. “That’s what I should have done before I did anything else.”

From THE GOLDEN HOUR: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood by Matthew Specktor. Copyright © 2025 by Matthew Specktor. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.